..so far, so good. So we now know we can get below the diaphragm with minimally invasive surgery but our limit is to the second lumbar vertebra....maybe the third.

..so far, so good. So we now know we can get below the diaphragm with minimally invasive surgery but our limit is to the second lumbar vertebra....maybe the third.LAST REVISED 20 May 2002

Ronald G Blackman MD

Write to: Dr. Blackman

1073 Hubert Road

Oakland, CA 94610

The best and easiest way to ask for information is to e-mail at this address.rgb@scoliosisrx.com

This paper is intended to inform you regarding the present status and technique that we developed and used. At the present time this technique has been used on over seventy children/adolescents and three adults.

So that we could gather our results the last case done was approximately October 2000.

Dr. Sanders in San Antonio, TX and Dr. Rieger in New Jersey continue to do this technique.

The disparity in numbers of children compared to adults is due to the nature of our practice and that our hospital is a children's hospital. If the opportunity arose, we have a number of local "adult type" hospitals available. Adults have the same anatomy. It's just that our practice is mainly with children. We do not feel this technique is useful at the present for anyone over 50 nor do we think it is useful for anyone who has a low curve ( in the lumbar area.) We are able to do the procedure below the diaphragm now to reach to L2 or L3 . In January 99 we did our first and second cases of "thoracolumbar scoliosis". They were quite successful

..so far, so good. So we now know we can get below the diaphragm with minimally invasive surgery but our limit is to the second lumbar vertebra....maybe the third.

..so far, so good. So we now know we can get below the diaphragm with minimally invasive surgery but our limit is to the second lumbar vertebra....maybe the third.

In children we have found that this is not the best approach for correction of scoliosis in very young children since the vertebra are too small and not hard enough to hold the screws. This may be somewhere around age 8 -10 years [we have done a couple of 10 year olds successfully]. Similarly children with neuromuscular scoliosis are also not good candidates since the stresses on the bones are tremendous and usually the vertebra are not hard due to the inactivity. Standing, walking and running all contribute to strong vertebra and if this process is missing then the bones do not get hard enough; and firm bone is needed to accept and hold the screws.

It is not designed to relieve pain nor do any other magic. It is designed to stabilize thoracic curves [and now thoracolumbar] with a minimal incision and with resulting minimal pain and superior recovery. In the process we try to get correction of the curve , as much as possible.

Initially we were very enthusiastic and our initial results seemed excellent. The results still are satisfactory but as we get into the longer term follow up the results do not seem to be as good as newer techniques developed since, afford the scoliosis patient. We have seen breakage of the rods due to failure of the fusion to become solid. This has always been a problem in anterior fusions and seems to remain a problem despite adequate fixation withe screws. In fact, the failure to fuse causes an increase in the curve, loosening of the screws and breakage of the rods somewhere in the one to two year followup in about 22% of our patients. This , in and of itself may not be a disaster, but usually requires a second procedure. Many cases would normally have a second procedure since the major reason for going in anteriorly is to remove the discs and loosen up the spine to get better correction. A separate paper discusses our results for patients followed for more than two years.

Anterior spinal instrumentation and fusion for correction of scoliosis has been a standard approach for at least the last 45 years. Over this period of time it has become apparent that the advantages are that inclusion of fewer segments are required for correction of the curve so mobility of the lumbar spine is preserved and faster healing of the interbody fusion occurs compared to posterior fusion. Additionally, it has been shown that removal of the discs anteriorly allows a more flexible spine leading to better correction of the scoliosis. The major disadvantage has been the long thoracotomy scar which is quite visible.

Seven years ago we started research leading to endoscopic release of the anterior longitudinal ligament of the vertebral body coupled with discectomy of the thoracic spine. We felt that an endoscopic approach [much as is used for knee surgery or gall bladder surgery] would allow a more complete discectomy, particularly above and below the apex of the curve, leading to an increase in the final correction of the curve with a decrease in the morbidity normally associated with this procedure.

In the standard thoracotomy, the apex of the curve can be adequately exposed, but above and below the apex the disc spaces are not parallel to the exposure view and instruments needed to remove the discs and the end plates cannot adequately perform this function. This may partially explain the relatively high incidence of non union at the upper level of open fixation. The entry of the instruments into the disc spaces need to be in line, or parallel, with the discs.

In the standard thoracotomy, the apex of the curve can be adequately exposed, but above and below the apex the disc spaces are not parallel to the exposure view and instruments needed to remove the discs and the end plates cannot adequately perform this function. This may partially explain the relatively high incidence of non union at the upper level of open fixation. The entry of the instruments into the disc spaces need to be in line, or parallel, with the discs.

Insertion of the instruments through small additional incisions can and have been done in addition to the thoracotomy incision. Once this rationale for additional incisions was agreed upon then the completely endoscopic approach became logical. In addition to being able to do a more complete discectomy it was hoped that the smaller incisions without rib removal would lead to faster recovery, less pain, shorter hospitalization plus a more acceptable cosmetic result as to the surgical scar.

Because most of these surgical procedures have been associated with posterior spinal fusions, these hypotheses have been difficult to prove. In those cases where we did anterior and posterior fusion for congenital scoliosis, hospital stay did appear to be shorter as did recovery time to full activity. We evaluated forty cases of multilevel anterior endoscopic discectomy for scoliosis. The anterior discectomy was performed to increase mobility of the spine and amount of correction and the posterior fusion and instrumentation was to partially correct and hold the curve for fusion purposes. We were able to consistently improve the correction to past the bending correction by a significant amount and that total curve correction in these stiff curves average 64% correction. But, we also noted that we did not change the recovery rate of the pulmonary function to normal compared to that seen in open thoracotomy with posterior fusion or posterior fusion alone. It would seem that posterior fusion is the major influence in long term decreased pulmonary function post-operatively.

There was no doubt in our minds that the four or five two centimeter incisions were cosmetically better than the long thoracotomy scar. Scientifically, beauty still remains in the eye of the beholder and we certainly can't measure this.

With these developments and the experience of over sixty endoscopic spine procedures, we realized that discectomy was only half of the procedure and that if we could not only loosen up the spine but correct it through these same four to six incisions we would eliminate the disadvantages of posterior fusion and really see the full advantages of endoscopic scoliosis surgery. After another year of developing techniques and instrumentations we performed our first endoscopic correction ( January 1997). We are now reporting the results of our first sixty cases. We realize our follow up is still short to claim total success; the rods may break, screws could pull out, fusion may not be achieved and will the shorter fusion hold up over time or need to be extended? But, there is no doubt that we have achieved the technical ability to insert six or seven screws and a rod , connect them together, compress the screws and achieve significant correction of the thoracic curve - through small two centimeter incisions in place of the large thoracotomy incision in previous years.

Needed instruments include a 30 degree and a 45 degree ten millimeter endoscope, 3-chip video camera, a selection of long curettes, pituitary rongeurs, Kerrison rongeurs and standard endoscopic surgical instruments. The levels for fixation have previously been determined by upright and bending films. This usually encompasses 6 or 7 levels between the fourth thoracic and the twelfth thoracic vertebra. The discs are identified, cleaned of overlying tissue and then incised and then excised.

Needed instruments include a 30 degree and a 45 degree ten millimeter endoscope, 3-chip video camera, a selection of long curettes, pituitary rongeurs, Kerrison rongeurs and standard endoscopic surgical instruments. The levels for fixation have previously been determined by upright and bending films. This usually encompasses 6 or 7 levels between the fourth thoracic and the twelfth thoracic vertebra. The discs are identified, cleaned of overlying tissue and then incised and then excised.

We usually leave the anterior longitudinal ligament but do as complete a discectomy as we can - within the limitations of leaving the head of the rib intact and in place. The cartilaginous end plates are removed. Bleeding , if any, is controlled with electrocautery and packing of the bleeding end plates with Surgicellr.

We usually leave the anterior longitudinal ligament but do as complete a discectomy as we can - within the limitations of leaving the head of the rib intact and in place. The cartilaginous end plates are removed. Bleeding , if any, is controlled with electrocautery and packing of the bleeding end plates with Surgicellr.

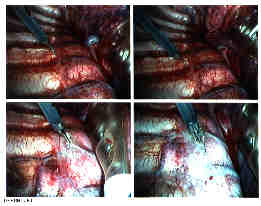

Insertion of screws into the vertebral bodies is then done under combined Xray control and endoscopic visualization. It is difficult to guess the correct inclination of the screw by looking into the pleural cavity at the exterior of the vertebral body. Correct placement obviously is essential. We use a cannulated screw and cannulated instruments which go over a Kirschner wire. The wire has a screw thread tip . Placing the initial wire not only gives us control over the superior /inferior inclination but also locks in the starting point and the anterior to posterior relationship as well.

The segmental vessels have been left intact since they form an anatomical landmark for the mid part of the vertebral body. We have been able to move the vessels to one side and then place our wire where the vessels were, without compromise to the vessels and no bleeding. They are thus left intact. The space just anterior to the head of the rib is then cleaned and the "K" wire is drilled through a starter guide from a posterior to slightly anterior direction. Visualizing it on the image intensifier low exposure fluoroscopy) confirms the correct placement. Visualizing it through the endoscope confirms the relationship to the anterior part of the spine, and the disc space and the more medial side of the vertebral body.

The segmental vessels have been left intact since they form an anatomical landmark for the mid part of the vertebral body. We have been able to move the vessels to one side and then place our wire where the vessels were, without compromise to the vessels and no bleeding. They are thus left intact. The space just anterior to the head of the rib is then cleaned and the "K" wire is drilled through a starter guide from a posterior to slightly anterior direction. Visualizing it on the image intensifier low exposure fluoroscopy) confirms the correct placement. Visualizing it through the endoscope confirms the relationship to the anterior part of the spine, and the disc space and the more medial side of the vertebral body.

Once proper "K" wire placement is done, the vertebral body is tapped and a screw placed. Ideally, the screw should reach to the opposite cortex and penetrate. The side walls of the screw are adjusted to be in alignment for receipt of the rod. This procedure is done at each level. In order to come in at the correct angle, one skin port may be used to go both above and below a rib; giving in essence two approaches through one skin incision.

Once proper "K" wire placement is done, the vertebral body is tapped and a screw placed. Ideally, the screw should reach to the opposite cortex and penetrate. The side walls of the screw are adjusted to be in alignment for receipt of the rod. This procedure is done at each level. In order to come in at the correct angle, one skin port may be used to go both above and below a rib; giving in essence two approaches through one skin incision.

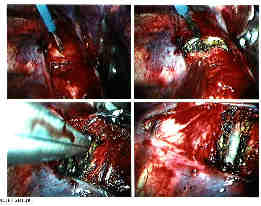

Following placement of the screws a 4.5mm rod is introduced into the pleural cavity. The rod has a slight flexibility and is usually left straight. The rod is manipulated onto the bottom screw and held in place by the top "capture" screw. Only a small amount of rod is left distally to avoid damage to the diaphragm. The rod is then successively reduced into the screws and the top capture screws applied.

Following placement of the screws a 4.5mm rod is introduced into the pleural cavity. The rod has a slight flexibility and is usually left straight. The rod is manipulated onto the bottom screw and held in place by the top "capture" screw. Only a small amount of rod is left distally to avoid damage to the diaphragm. The rod is then successively reduced into the screws and the top capture screws applied. Once the rod is fully reduced onto the screws and held in place, compression between the screws is done using an external compression device. The top capture screws are successively tightened after compression.

Once the rod is fully reduced onto the screws and held in place, compression between the screws is done using an external compression device. The top capture screws are successively tightened after compression.

Once correction has been achieved our final attention is to try to ensure a fusion. Using a curette, the end plates are further destroyed leaving the cancellous bone particles in place between the end plates.

Finally, bone graft from a small portion of the rib is morselised and placed into the disc spaces or a bone gel from the bone bank is squeezed into the disc space. The sulcus between the pleura and the lung is suctioned and we check to make sure there is no bleeding. A #20 straight chest tube is inserted primarily for drainage of fluid from the raw bleeding bone surfaces. Wounds are, of course, closed and the patient is extubated.

Finally, bone graft from a small portion of the rib is morselised and placed into the disc spaces or a bone gel from the bone bank is squeezed into the disc space. The sulcus between the pleura and the lung is suctioned and we check to make sure there is no bleeding. A #20 straight chest tube is inserted primarily for drainage of fluid from the raw bleeding bone surfaces. Wounds are, of course, closed and the patient is extubated.

This procedure is highly dependent on skilled anesthesia. One lung ventilation is almost always necessary so skillful intubation of the concave side main stem bronchus either with a double lumen endotracheal tube, or with a single tube placed by fiberoptic scope is needed. Changes in oxygen saturation during the procedure must be dealt with by re-evaluating endotracheal tube placement since slight shifts of the tube can lead to significant changes of oxygen saturation levels and/or lung aeration on the working side.

At the end of the procedure the lung needs to be re-inflated and both lungs need to be well suctioned. Any suggestion of mucous plugs must be dealt with by bronchoscopy. We have noted more postoperative atelectasis on the ventilated side than on the unaerated side. Postoperatively the patient must do lung exercises from the very start Since no rib removal has been performed there is less pain than expected and our patients have performed this task well.

Some specifics in performing this procedure are in order. The surgeon performing this procedure stands at the patients' back. This allows screw placement in the correct direction - away from the spinal cord. In making the comment about "the surgeon" there should be no mistaking the fact this is a team surgical endeavor. There is no place for the egotistical surgeon since each person plays a vital role in the flow of the procedure and the successful outcome.

The screws used are titanium cancellous screws but will perforate the opposite cortex. They appear to have good holding power in the bone. Experiments are being undertaken to quantify the actual holding power in comparison to other screws but we have placed the screws into relatively osteoporotic bone and have been unable pull them out with 60 pound pull. The screws are made with a blunt tip since the major structure on perforating the bone is the segmental vessels on the opposite cortex.

The screws used are titanium cancellous screws but will perforate the opposite cortex. They appear to have good holding power in the bone. Experiments are being undertaken to quantify the actual holding power in comparison to other screws but we have placed the screws into relatively osteoporotic bone and have been unable pull them out with 60 pound pull. The screws are made with a blunt tip since the major structure on perforating the bone is the segmental vessels on the opposite cortex.

We have performed more than sixty of these procedures. We are reporting on our first sixty.All but three are persons in the age group 10 through 19. The three were adults between 20 and 35. Curve sizes have ranged from 98 to 38 degree in the thoracic spine with compensatory curves of a similar degree. The majority of the curves were in the 60 - 65 degree range with relatively stiff curves as shown on bending films. Correction greater than the bending amount has been achieved in all but three cases.

We have performed more than sixty of these procedures. We are reporting on our first sixty.All but three are persons in the age group 10 through 19. The three were adults between 20 and 35. Curve sizes have ranged from 98 to 38 degree in the thoracic spine with compensatory curves of a similar degree. The majority of the curves were in the 60 - 65 degree range with relatively stiff curves as shown on bending films. Correction greater than the bending amount has been achieved in all but three cases.

The ten year old boy in case #6 had a curve of 98 degrees which bent out to 75 degrees with a final surgical correction to 45 degrees. Five screws over six levels were instrumented.

The ten year old boy in case #6 had a curve of 98 degrees which bent out to 75 degrees with a final surgical correction to 45 degrees. Five screws over six levels were instrumented.

Statistics are meaningless in these sixty cases except for trends and we definitely have shown that it is possible to correct curves from 60-65 degrees down to 15-20 degrees through this approach. Just as gratifying is the post operative recovery.Our patients appear alert the day following surgery; most have been talkative, a few even smiling. On their second postoperative day they were usually out of bed and up in a chair. A number of patients have walked around the first day after surgery! By the third day most patients are walking around and discharged home between the third and fifth postoperative day, with the IVs out and on mild pain medication and eating.[Not all! - there are always exceptions in which we encounter persons with more pain/discomfort than usual and take an extra few days to recover]

FOR A FULL DISCUSSION OF OUR RESULTS AT TWO YEARS OF FOLLOW-UP PLEASE SEE OUR Results at two years This has been linked at the top and bottom of this paper also for convenience.

Our average correction was 62 percent initially which has dropped to about 58 percent after one year. Five patients lost greater than 5 degrees in that year...two lost seven degrees and one lost nine degrees. Two others lost a significant 16 degrees. One of them had fantastic correction down to 7 degrees and so ended up with a curve that was initially 67 degrees and ended up 23 degrees. quite acceptable) and one lost all correction and was back at her pre-operative level of 45 degrees - most disappointing and the reason for this loss was hard to determine. Posterior surgery has, of course, its problems and certainly occasionally one does not get the correction hoped for whether done the standard posterior was or the newer methods.

We have seen broken rods as a result of failure to fuse. I suspect that ten patients have not fused solidly at the upper vertebral level and their rods will ultimately fail. This compares with a 12 percent non union rate done anteriorly with a standard technique. Four patients have had the little top capture screw that holds the rod in place, come loose - and these are four who I suspect have non-union of the fusion. At this time though, no apparent harm has occurred . The rod is intact , but the angle of the curve has changed and while there is no discomfort the increase in the curve has led to a repeat surgery -- usually a standard posterior fusion with return of the excellent correction.

Blood loss during surgery is about 150 ccs. Blood loss postoperatively, a mixture of serous fluid and blood, via a chest tube has been approximately 350 cc over the 48 hours the chest tube was left in. No patients received any transfusion and we no longer ask our patients to donate blood for their surgery.

Pain control was achieved with intrathecal morphine followed by intravenous morphine. Oral analgesics were substituted for morphine between 48 and 72 hours after surgery.

Many of the sixty noted numbness over the breast and anterior chest area which was resolving by the time of discharge and completely resolved by the 6 week follow up visit. One has lingering numbness almost a year later.

Once home, all patients were ambulatory and able to return to light activities within a week. Walking around the block, visiting classmates in school came rapidly. Parents were equally pleased with the rapid return to normal of their child. But, since we have more experience than the parents in being able to compare pre-endoscopic recovery compared to endoscopic surgical recovery, we also have to rate those children having endoscopic surgery as returning to a light activity lifestyle far earlier than our previous surgical patients. Our nurses on the pediatric floor comment that they hope we wont go back to the old way!But the "old way" is never really the old way and posterior fusion has a lot going for it.

Occasionally we have needed to enlarge one of the incisions for technical reasons. This then would be considered an endoscopic "assisted" procedure. This is sometimes done when "one lung" anesthesia doesn't work out or when we go down "low". The trade off is that the other incisions can be made by pulling the skin up or down and not having to make more than one or two smaller incisions. All the benefits of the procedure remain; better visualization, better access to the vertebra, a more in-line approach to removing the discs and putting in the screws.

We have described a new approach to an old problem. We may have made it sound easy. It isn't! During this evolution each case brought with it one or two problems and in each we found or devised a solution only to have a new or different problem arise for the next case. None of these problems jeopardized either the patient nor the result. Sometime the result was an increase in the operating time, often an increase in our own blood pressure, sometimes an extra incision solved the problem or the use of a different tool; and ultimately the design and manufacture of our present screw, rod and equipment.

We have devised techniques to correct these problems and hopefully they will not recur. However, as in any surgery, that is looked at introspectively, we are always adjusting the technique to accommodate changes in anatomy, changes in our patients responses and other unforeseen problems. We are sure that we shall have to continue along that path.

We have accomplished what we set out to do. Good correction of the curve with inclusion of far fewer vertebra than we would have done, had the procedure been a posterior approach. We produced a very acceptable scar, without harming the chest wall. We have seen a much faster recovery and our patients and their families have been extremely happy with the decreased hospital stay, decrease in pain over their expectations and without a doubt, the smaller incisions.

Xray picture of endoscopically placed screws

Xray picture of endoscopically placed screws

Discussion of Results at Two Years.

Return to Main Page - Discussion of Scoliosis

Names of physicians trained in this technique.

Dr. Mark Rieger

The Orthopedic Center

218 Ridgedale Ave

Cedar Knolls,NJ 07927

ph: 973 538 7700

Dr. Albert Sanders

Christius Santa Rosa Health Care

519 West Houston Street

San Antonio, TX

ph: 210 704 2122